Papers & Publications

Publications

Sabine C. Carey, Christian Gläßel and Katrin Paula. 2025. “Media impact on perceptions in postwar societies: Insights from Nepal”. Conflict Management and Peace Science 42(4):394-417.

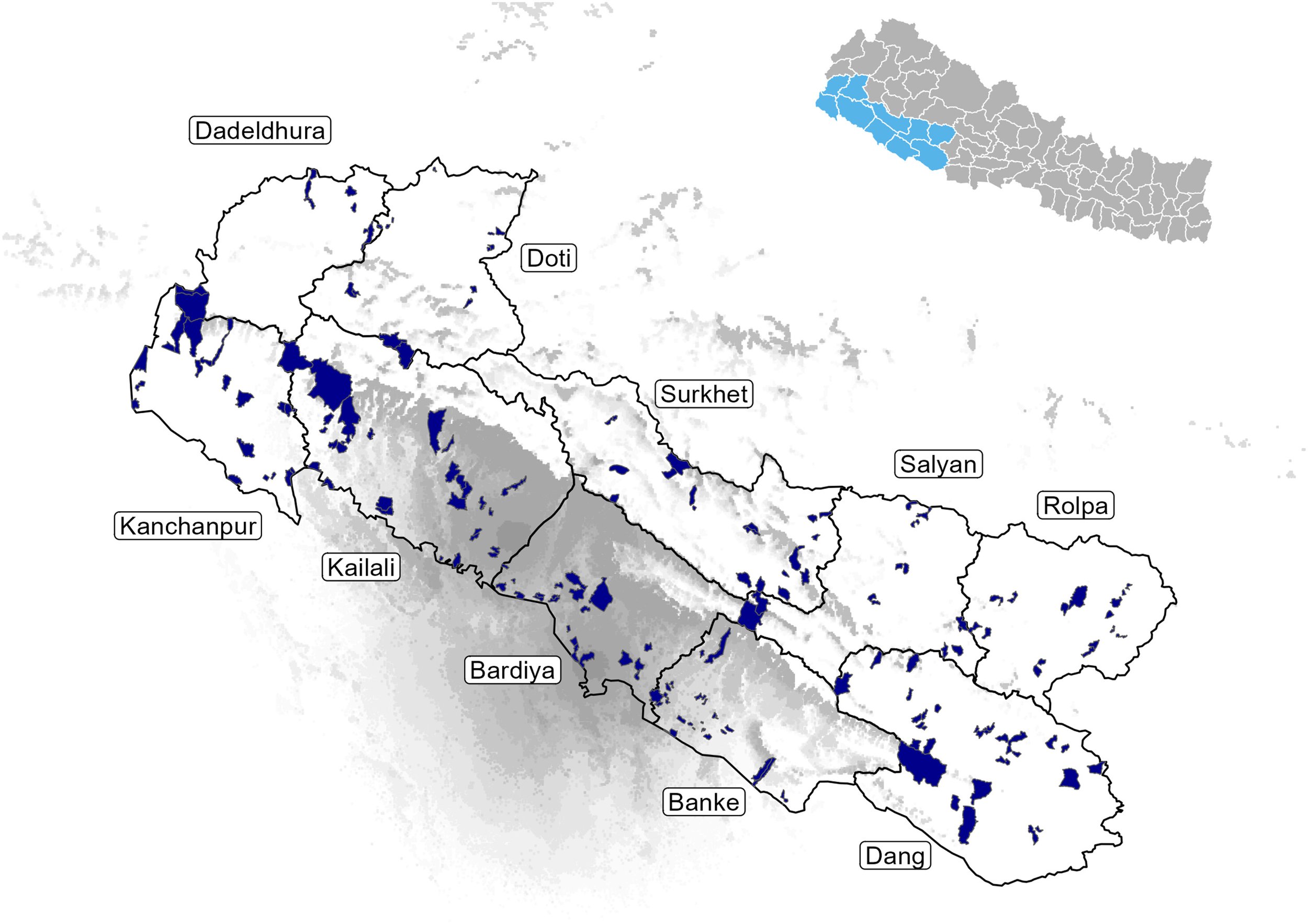

Figure 1. Sampled wards and Fulbari FM Radio signal strength level

Can media have a lasting impact on attitudes in postwar countries? A lingering impact of media could substantially shape peace and security in postwar societies. Our quasi-experimental research design and original survey data utilize variation in the reception of an anti-government radio station in Nepal's Terai region, which was shut down after violent clashes. Our results show that individuals with access to anti-government broadcasts were less optimistic about peace, police and civic activism three years after the closure of the station. The study has implications for understanding the longer-term role of media for post-conflict attitudes and state-building.

Responses to “Which of these, if any, do you think currently pose a severe risk to your personal security?”

Contested borders raise the question of how to provide security without provoking a stronger neighbor. Using novel survey data from Georgia, we investigate how proximity to disputed borderlines and variation in the nature of borderlines shape security perceptions and foreign policy preferences. People near the ambiguous border to South Ossetia are substantially more likely to worry about border insecurity than those near the fortified borderline to Abkhazia. Yet those near South Ossetia are least likely to demand a stronger stance against Russian supported creeping borderization and are not consistently more in favor of a stronger alliance with NATO. This exploratory study points to important within-country variation and that those most affect by instability do not necessarily favor more hawkish foreign policies.

Sabine C. Carey, Belén González and Neil J. Mitchell. 2023. “Media freedom and the escalation of state violence.” Political Studies 71(2): 440-462.

Note: Points represent change in the Pr(De-escalation) in grey and change in the Pr(Escalation) in black as opposed to “no change” in the government’s repressive behaviour. The remaining variables are held at their mean or median.

When governments face severe political violence, they regularly respond with violence. Yet not all governments escalate repression under such circumstances. We argue that to understand the escalation of state violence, we need to pay attention to the potential costs leaders might face in doing so. We expect that the decision to escalate state violence is conditional on being faced with heightened threats and on possessing an information advantage that mitigates the expected cost of increasing state violence. In an environment where media freedom is constrained, leaders can deny or reframe an escalation of violations and so expect to reduce potential domestic and international costs attached to that decision. Using a global dataset from 1981-2006, we show that state violence is likely to escalate in response to increasing violent threats to the state when media freedom is curtailed—but not when the media are free from state intervention. A media environment that the government knows is free to sound the alarm is associated with higher political costs of repression and effectively reduces the risk of escalating state violence, even in the face of mounting armed threats.

Click here for the open access article.

Sabine C. Carey, Belén González and Christian Gläßel. 2022. “Divergent perceptions of peace in post-conflict societies: Insights from Sri Lanka.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 66(9): 1589-1618.

In this study we investigate how members of opposing sides experience peace a decade after a decisive victory of the majority. Using original survey data from a representative sample of 2,000 respondents in 2018 Sri Lanka, we find that even one decade after the conflict members of the Sinhalese winning majority are consistently more likely to report improvements in peace than Tamils, who were represented by the defeated minority. But the benefit of a ``victor's peace'' does not seem to translate into an optimistic outlook of the victorious group, nor does it increase people's endorsement for repressive state measures. Despite the drastically improved physical security for the defeated ethnic minority since the war, they experience a deterioration in other dimensions of peace.

Click here for the article.

Note: Effect of ethnicity on perceived changes in elements of peace

Sabine C. Carey, Neil J. Mitchell and Katrin Paula. 2022. “The Life, Death and Diversity of Pro-Government Militias: The Fully Revised Pro-Government Militias Database Version 2.0.” Research & Politics 9(1)

Figure 2. Distribution of pgms across countries and time

This article presents version 2.0 of the Pro-Government Militias Database (PGMD). It is increasingly clear that it is untenable to assume a unified security sector, as states often rely on militias to carry out security tasks. The PGMD 2.0 provides new opportunities for studying questions such as when states rely on militias, how they chose among different types and the consequences for stability and peace. We detail how the PGMD 2.0 provides new information on the characteristics, behaviour, life cycle and organization of 504 pro-government militias across the globe between 1981 and 2014.

Sabine C. Carey. “The promises and perils of pro-government militias in armed conflicts.” PEACELAB Blogpost, Global Public Policy Institute, 14 April 2021.

Pro-government militias are frequently involved in armed conflict. While they offer certain advantages such as localized knowledge, they often become agents of violence and spoil peace processes. The German government should be aware of these risks in its crisis engagement and support efforts that aim at ensuring accountability and creating targeted disarmament programs.

Sabine C. Carey and Anita R. Gohdes. 2021. “Understanding journalist killings.” The Journal of Politics 83(4): 1216-1228.

Change in probability of a journalist being killed, given change from not elected to elected local government, in: carey and gohdes forthcoming.

Why do state authorities murder journalists? We show that the majority of journalists are killed in democracies and present an argument that focuses on institutional differences between democratic states. In democracies, journalists will most likely be targeted by local state authorities that have limited options to generally restrict press freedom. Where local governments are elected, negative reporting could mean that local politicians lose power and influence, especially if they are involved in corrupt practices. Analyzing new global data on journalist killings that identify the perpetrator and visibility of the journalist, we show that local-level elections carry an inherent risk, particularly for less visible journalists. Killings perpetrated by criminal groups follow a similar pattern to those by state authorities, pointing to possible connections between these groups. Our study shows that without effective monitoring and accountability, national democratic institutions alone are unable to effectively protect journalists from any perpetrator.

Click here for the accepted paper and the online appendix.

Sabine C. Carey and Belén González. 2021. “The legacy of war: The effect of militias in postwar repression.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 38(3): 247-269.

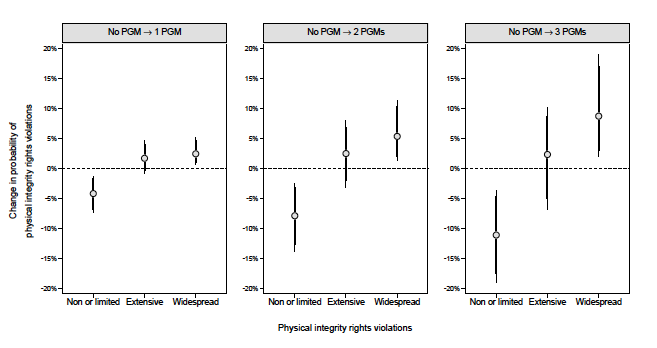

The effect of conflict inherited government militias on repression, in: Carey and González forthcoming.

How do wartime legacies affect repression after the conflict ends? Irregular forces support the government in many civil wars. We argue that if this link continues after the war, respect for human rights declines. As “tried and tested" agents they are less likely to shirk when given the order to repress. Governments might also keep the militias as a “fall-back option", which results in more repression. Analyzing data from 1981 to 2014 shows that pro-government militias (PGMs) that were inherited from the previous con ict are consistently associated with worse repression, but newly created ones are not. Wartime PGMs target a broader spectrum of the population and are linked to worse state violence. New militias usually supplement wartime ones and use violence primarily against political opponents. This study highlights the detrimental impact of war legacies.

Click here for the open access article, the online appendix and replication files (zip folder).

Mascha Rauschenbach and Katrin Paula. 2019. “Intimidating voters with violence and mobilising them with clientelism.” Journal of Peace Research 56(5): 682-696. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343318822709

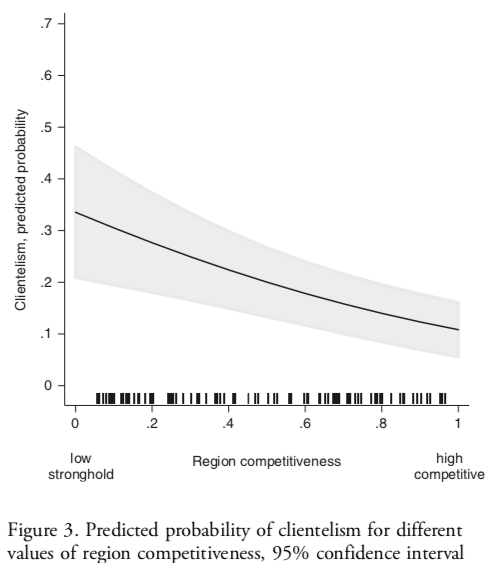

Rauschenbach and Paula JPR forthcoming

Recent research suggests that intimidating voters and electoral clientelism are two strategies on the menu of manipulation, often used in conjunction. We do not know much, however, about who is targeted with which of these illicit electoral strategies. This article devises and tests a theoretical argument on the targeting of clientelism and intimidation across different voters. We argue that in contexts where violence can be used to influence elections, parties may choose to demobilize swing and opposition voters, which frees up resources to mobilize their likely supporters with clientelism. While past research on this subject has either been purely theoretical or confined to single country studies, we offer a first systematic cross-national and multilevel analysis of clientelism and voter intimidation in seven African countries. We analyze which voters most fear being intimidated with violence and which get targeted with clientelistic benefits, combining new regional-level election data with Afrobarometer survey data. In a multilevel analysis, we model the likelihood of voters being targeted with either strategy as a function of both past election results of the region they live in and their partisan status. We find that voters living in incumbent strongholds are most likely to report having being bribed in elections, whereas those living in opposition strongholds are most fearful of violent intimidation. We further provide suggestive evidence of a difference between incumbent supporters and other voters. We find support that incumbent supporters are more likely to report being targeted with clientelism, and mixed support for the idea that they are less fearful of intimidation. Our findings allow us to define potential hot spots of intimidation. They also provide an explanation for why parties in young democracies concentrate more positive inducements on their own supporters than the swing voter model of campaigning would lead us to expect. Click here for the article.

Christoph V. Steinert, Janina I. Steinert and Sabine C. Carey. 2019. "Spoilers of peace: Pro-government militias as risk factors for conflict recurrence." Journal of Peace Research 56(2): 249-263.

This study investigates how deployment of pro-government militias (PGMs) as counterinsurgents affects the risk of conflict recurrence. Militiamen derive material and non-material benefits from fighting in armed conflicts. Since these will likely have diminished after the conflict’s termination, militiamen develop a strong incentive to spoil post-conflict peace. Members of pro-government militias are particularly disadvantaged in post-conflict contexts compared to their role in the government’s counterinsurgency campaign. First, PGMs are usually not present in peace negotiations between rebels and governments. This reduces their commitment to peace agreements. Second, disarmament and reintegration programs tend to exclude PGMs, which lowers their expected and real benefits from peace. Third, PGMs might lose their advantage of pursuing personal interests while being protected by the government, as they become less essential during peace times. To empirically test whether conflicts with PGMs as counterinsurgents are more likely to break out again, we identify PGM counterinsurgent activities in conflict episodes between 1981 and 2007. We code whether the same PGM was active in a subsequent conflict between the same actors. Controlling for conflict types, which is associated with both the likelihood of deploying PGMs and the risk of conflict recurrence, we investigate our claims with propensity score matching, statistical simulation and logistic regression models. The results support our expectation that conflicts in which pro-government militias were used as counterinsurgents are more likely to recur. Our study contributes to an improved understanding of the long-term consequences of employing PGMs as counterinsurgents and highlights the importance of considering non-state actors when crafting peace and evaluating the risk of renewed violence.

Download the open access article here. [replication data].

Anita R. Gohdes and Sabine C. Carey. 2017. "Canaries in a Coal Mine: What the killings of journalists tell us about future repression." Journal of Peace Research 54(2): 157-174.

Can the government's infringements of the rights of journalists tell us anything about its wider human rights agenda? The killing of a journalist is a sign for deteriorating respect for human rights. If a government orders the killing of a journalist, it is willing to use extreme measures to eliminate the threat posed by the uncontrolled flow of information. If non-state actors murder journalists, it reflects insecurity, which can lead to a backlash by the government, again triggering state-sponsored repression. We introduce a new global dataset on killings of journalists between 2002 and 2013, which uses three different sources that track such events across the world. The new data show that mostly local journalists are targeted and that in most cases the perpetrators remain unconfirmed. Particularly in countries with limited repression, human rights conditions are likely to deteriorate in the two years following the killing of a journalist. When journalists are killed, human rights conditions are unlikely to improve where standard models of human rights would expect an improvement.

Go to the ungated article, a related Monkey Cage post, a report by the European Commission or a podcast on Global Dispatches.

Sabine C. Carey and Neil J. Mitchell. 2017. "Pro-government Militias" Annual Review of Political Science 20: 127-147.

Sociologists, political scientists, and economists have long emphasized the benefits of monopolizing violence and the risks of failing to do so. Yet recent research on conflict, state failure, genocide, coups, and election violence suggests governments cannot or will not form a monopoly. Governments worldwide are more risk acceptant than anticipated. They give arms and authority to a variety of nonstate actors, militias, vigilantes, death squads, proxy forces, paramilitaries, and counterbalancing forces. We develop a typology based on the links of the militia to the government and to society as a device to capture variations among these groups. We use the typology to explore insights from this emerging literature on the causes, consequences, and puzzling survival of progovernment militias and their implications for security and human rights, as well as to generate open questions for further research.

Download the pre-proof version of the paper here or go to the ARPS site.

Sabine C. Carey, Neil J. Mitchell and Adam Scharpf. 2016. "Pro-Government Militias and Conflict." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.33. Last modified February 24, 2022.

Counterinsurgency war duration with + without local PGMs, 1945-2005.

Pro-government militias are a prominent feature of civil wars. Governments in Ukraine, Russia, Syria, and Sudan recruit irregular forces in their armed struggle against insurgents. The United States collaborated with Awakening groups to counter the insurgency in Iraq, just as colonizers used local armed groups to fight rebellions in their colonies. A now quite wide and established cross-disciplinary literature on pro-government nonstate armed groups has generated a variety of research questions for scholars interested in conflict, political violence, and political stability: Does the presence of such groups indicate a new type of conflict? What are the dynamics that drive governments to align with informal armed groups and that make armed groups choose to side with the government? Given the risks entailed in surrendering a monopoly of violence, is there a turning point in a conflict when governments enlist these groups? How successful are these groups? Why do governments use these nonstate armed actors to shape foreign conflicts, whether as insurgents or counterinsurgents abroad? Are these nonstate armed actors always useful to governments or perhaps even an indicator of state failure? How do pro-government militias affect the safety and security of civilians?

The enduring pattern of collaboration between governments and pro-government armed groups challenges conventional theory and the idea of an evolutionary process of the modern state consolidating the means of violence. Research on these groups and their consequences began with case studies, and these continue to yield valuable insights. More recently, survey work and cross-national quantitative research have contributed to our knowledge. This mix of methods is opening new lines of inquiry for research on insurgencies and the delivery of the core public good of effective security. [Dataset]

Sabine C. Carey and Neil J. Mitchell. 2016. "Pro-Government Militias, Human Rights Abuses and the Ambiguous Role of Foreign Aid." German Development Institute Briefing Paper 4/2016, DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.2119.0167; German version.

Many governments worldwide make use of unofficial armed groups. This practice substantially increases the risks for civilians, as the activities of such pro-government militias (PGMs) are usually accompanied by a higher level of human rights violations, including killings, torture and disappearances. This briefing paper shows that PGMs exist not only in failed states, poor countries or those engulfed in civil war and armed conflict. They can also be found in more or less democratic governments and are most common in semi-democracies. The risks that PGMs bring for peace, security and stability can only be reduced if the international community knows how governments delegate security tasks and holds governments responsible for the violence that their various state and non-state agents commit.

Sabine C. Carey, Michael P. Colaresi and Neil J. Mitchell. 2016. "Risk Mitigation, Regime Security, and Militias: Beyond Coup-proofing." International Studies Quarterly. 60(1): 59-72.

In Thailand, India, Libya and elsewhere, governments arm the populace or call up volunteers in irregular armed groups despite the risks this entails. The widespread presence of these militias, outside the context of state failure, challenges the expectation that governments uniformly consolidate the tools of violence. Drawing on the logic of delegation, we resolve this puzzle by arguing that governments have multiple incentives to form armed groups with a recognized link to the state but outside of the regular security forces. Such groups off-set coup risks as substitutes for unreliable regular forces. Similar to other public-private collaborations, they also complement the work of regular forces in providing efficiency and information gains. Finally, these groups distance the government from the controversial use of force. These traits suggest that militias are not simply a sign of failed states or a precursor to a national military, but an important component of security portfolios in many contexts. Using cross-national data (1981-2005), we find support for this mix of incentives. From the perspective of delegation, used to analyze organizational design, global accountability and policy choices, the domestic and international incentives for governments to choose militias raise explicit governance and accountability issues for the international community.

Download paper and appendix.

Sabine C. Carey, Michael P. Colaresi and Neil J. Mitchell. 2015. "Governments, Informal Links to Militias, and Accountability." Journal of Conflict Resolution. 59(5): 850-876.

From Syria to Sudan, governments have informal ties with militias that use violence against opposition groups and civilians. Building on research that suggests these groups offer governments logistical benefits in civil wars as well as political benefits in the form of reduced liability for violence, we provide the first systematic global analysis of the scale and patterns of these informal linkages. We find over 200 informal state-militia relationships across the globe, within but also outside of civil wars. We illustrate how informal delegation of violence to these groups can help some governments avoid accountability for violence and repression. Our empirical analysis finds that weak democracies as well as recipients of financial aid from democracies are particularly likely to form informal ties with militias. This relationship is strengthened as the monitoring costs of democratic donors increases. Out-of-sample predictions illustrate the usefulness of our approach that views informal ties to militias as deliberate government strategy to avoid accountability.

Download ungated article.

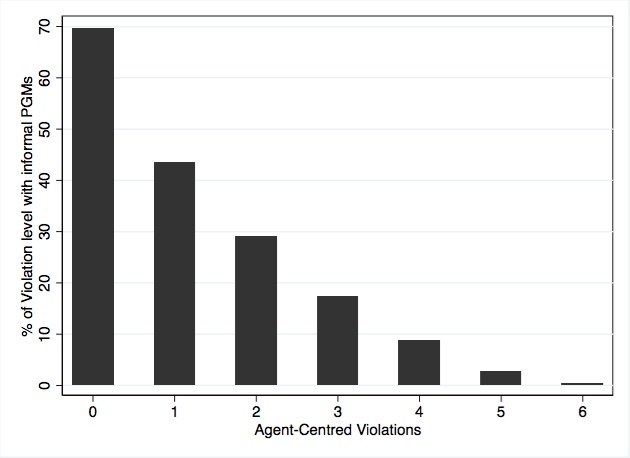

Neil J. Mitchell, Sabine C. Carey and Christopher Butler. 2014. "The Impact of Pro-Government Militias on Human Rights Violations." International Interactions: 40(5): 812-836.

New data show that between 1982-2007, in over 60 countries governments were linked to and cooperated with informal armed groups within their own borders. Given the prevalence of these linkages, we ask how such links between governments and informal armed groups influence the risk of repression. We draw on principal-agent arguments to explore how issues of monitoring and control help understanding of the impact of militias on human rights violations. We argue that such informal agents increase accountability problems for the governments, which is likely to worsen human rights conditions for two reasons. First, it is more difficult for governments to control and to train these militias and they may have private interests in the use of violence. Second, informal armed groups allow governments to shift responsibility and use repression for strategic benefits while evading accountability. Using a global dataset from 1982 to 2007, we show that pro-government militias increase the risk of repression and that the presence of militias also affects the type of violations that we observe.

Download ungated article.

Sabine C. Carey, Neil J. Mitchell and Will Lowe. 2013. "States, the Security Sector and the Monopoly of Violence: A New Database on Pro-Government Militias." Journal of Peace Research Vol 50(2): 249-258, 2013.

This paper introduces the global Pro-Government Militias Database (PGMD). Despite the devastating record of some pro-government groups, there has been little research on why these forces form, under what conditions they are most likely to act, and how they affect the risk of internal conflict, repression, and state fragility. From events in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, Sudan, or Syria and the countries of the Arab Spring we know that pro-government militias operate in a variety of contexts. They are often linked with extreme violence and disregard for the laws of war. Yet research, notably quantitative research, lags behind events. In this article we give an overview of the PGMD, a new global dataset that identifies pro-government militias from 1981 to 2007. The information on pro-government militias (PGMs) is presented in a relational data structure, which allows researchers to browse and download different versions of the dataset and access over 3,500 sources that informed the coding. The database shows the wide proliferation and diffusion of these groups. We identify 332 PGMs and specify how they are linked to government, for example via the governing political party, individual leaders, or the military. It captures the proximity of the groups to the government by distinguishing between informal and semi-official militias. It identifies, among others, membership characteristics and the types of groups they target. These data are likely to be relevant to research on state strength and state failure, the dynamics of conflict, including security sector reform, demobilization and reintegration, as well as work on human rights and the interactions between different state and non-state actors. To illustrate uses of the data, we include the PGM data in a standard model of armed conflict and find that such groups increase the risk of civil war.